Features

David Browne & The Lost Story Of 1970

by Curtis Jones

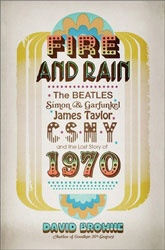

In his 40-years-later look back at the year 1970, Rolling Stone writer David Browne takes us on a trip back to a year that looms large in rock memory but—unlike 1964 (the British Invasion) or 1967 (the “Summer Of Love”)—does not capture the collective imagination. Yet Browne argues that 1970 was the year everything shifted: the year that signaled that the ’60s were most definitely over, and the comfort of the mainstay bands everyone was accustomed to was yanked out from underneath. His tome with the phenomenally long full title of Fire And Rain: The Beatles, Simon & Garfunkel, James Taylor, CSNY, And The Lost Story of 1970 (thank goodness for the CSNY abbreviation) tries to bring together the disparate threads from that year that music lovers and 20th century historians know and make sense of it all.

In his 40-years-later look back at the year 1970, Rolling Stone writer David Browne takes us on a trip back to a year that looms large in rock memory but—unlike 1964 (the British Invasion) or 1967 (the “Summer Of Love”)—does not capture the collective imagination. Yet Browne argues that 1970 was the year everything shifted: the year that signaled that the ’60s were most definitely over, and the comfort of the mainstay bands everyone was accustomed to was yanked out from underneath. His tome with the phenomenally long full title of Fire And Rain: The Beatles, Simon & Garfunkel, James Taylor, CSNY, And The Lost Story of 1970 (thank goodness for the CSNY abbreviation) tries to bring together the disparate threads from that year that music lovers and 20th century historians know and make sense of it all.

When classic rock enthusiasts think of 1970, the obvious seismic shift in the music world that immediately comes to mind is the breakup of The Beatles. Any Beatles fan likely knows those details by heart. Yet Simon and Garfunkel also broke up in 1970; it’s just that their story was not as dramatic as the Beatles soap opera. Instead, the pair’s partnership seemed to fade out of existence similarly to the way they faded in. At the same time, another group’s presence seemed to multiply as Crosby, Stills, & Nash, after a powerhouse eponymous album in 1969, added Young and rode into 1970 looking like an unstoppable force. Meanwhile, like his guitar playing, James Taylor began a gentle but steady ascent up the charts with his second album, Sweet Baby James.

Browne casts these artists, and the four albums they put out that year (Let It Be, Bridge Over Troubled Water, Déjà Vu, and Sweet Baby James) as illustrations of the musical and cultural turning points reached in 1970. He has an obvious love for these artists and for their music, but the cultural aspect of the book is not romanticized at all. If anything, this book pulls back the curtain on the idealized revisionism the era has been given by baby boomers and the media. One would think that from 1967 until the end of the Vietnam War, it was all hippies and love with young college students activated to bring about the end of the war. Instead, Browne reminds readers that by 1970 the anti-war crowd had radicalized, with hundreds of homemade bombs being set off across the country by radical home-grown terror groups like the Weathermen. As these tactics increased, the rest of America moved toward Nixon or more moderate opposition, giving the president what he called his “silent majority” of supporters.

Within all of the turmoil of the year the ’60s died, cultural attitudes began to shift, and the music business began to transform as well. One year after Woodstock, festival organizers were having trouble both in pulling off an event and in raising enough money. With this, the power also began to shift from concert promoters, who had once been able to dictate ticket prices and venues, to the artists themselves. In 1970, small venues like the Fillmore East began to struggle against their capacity limits amid demands from artists for more money. Ticket prices rose, venues became larger, and millionaires were made.

While all the artists in the title are given their due in the book, there is an intense focus on CSNY. As evidenced from the acknowledgements, this is because members of this group made themselves available for copious interviews. As the material slants towards that group, it does offer an incredible insight into this group and their high-intensity pop flame that burned out entirely too soon. Just after CSN produced a highly successful first album, they began to work on a second. Even as the group was trying to record Déjà Vu, they were well on their way to breaking up as old tensions began to show through and ego and competitiveness rubbed emotions raw. It’s a wonder that they were able to produce such good music and last through a promotional tour (which as Browne lays out, they were barely able to do).

Browne argues that 1970 was a lost year—a year in which the idealism of the ’60s began to die and the doldrums of the ’70s began to peek through. The social turmoil with the Kent State shootings and hundreds of domestic terrorist bombings showed that something had gone awry. And while the powerhouse groups of the ’60s broke up to create several individual artists, music began to change too. Yet, Browne argues that the ascendency of James Taylor and the singer-songwriter pursuits of the other artists covered in the book, shows that America was searching for an escape from the events swirling around them. He argues they found this escape in the smooth sounds of artists like James Taylor, Carole King and Cat Stevens. This may be true to some extent, but it could also be argued that Americans turned to harder-edged groups like Black Sabbath and Led Zeppelin, who were starting to take off at the same time. Browne does not exactly answer his argument that these artists indicated what was to come in the ’70s decade, but his use of their stories is an excellent prism to evaluate the year that was 1970, and serves as a good intellectual starting point for the debate on cultural shifts and turmoil that would come in the following decade.