Liner Notes

Chris Squire: An Appreciation

by Jason Warburg

Another reason I’ve struggled to set these words down, though, is that this turn of events just seems so damned unreal, so fundamentally laws-of-nature-defying impossible. Never mind the announcement just six weeks ago that Squire had been diagnosed with Acute Erythroid Leukemia, a particularly merciless strain with a low survival rate. We’re talking about Chris bloody Squire here, a monumental figure in both progressive rock and bass playing circles for 45 years, a gentle giant of a man (there’s the clichés again) with a perpetual grin and boundless love of life. Men like Squire don’t simply disappear from this earth; they are too large in our minds and hearts for this to be even conceivable.

It is one of the inevitabilities of this era of rock, though. The musicians who broke new ground and led the way in the ’50s are mostly gone now, and those from the ’60s who are still around are increasingly frail. The headlines on the classic rock-focused news outlets I follow now chart the setbacks and losses of advancing age as often as they do new music or tours. The heroes of our youth may be heroes still, but they are not immortal.

And this is one of the lessons that being a four-decade fan of Chris Squire and the remarkable band he co-founded with singer Jon Anderson in a London pub in 1968 offers—our heroes, for all the magical powers we might wish to ascribe to them, are in the end made of the same stuff we are, flesh and blood, strengths and flaws. That is both what makes their talents seem so exceptional, and what surprises us again and again; they are both uncannily gifted, and perfectly ordinary.

Over the past four sad, remembrance-filled days, bandmate Geoff Downes has called Squire “legendary,” Genesis guitarist Steve Hackett said he “defined the progressive genre,” and no less a bass player than Geddy Lee of Rush cited him as “a huge inspiration to me.” Current Yes singer Jon Davison called him “the Jimi Hendrix of the bass guitar and a beautiful songwriter.”

Over the past four sad, remembrance-filled days, bandmate Geoff Downes has called Squire “legendary,” Genesis guitarist Steve Hackett said he “defined the progressive genre,” and no less a bass player than Geddy Lee of Rush cited him as “a huge inspiration to me.” Current Yes singer Jon Davison called him “the Jimi Hendrix of the bass guitar and a beautiful songwriter.”

All correct, of course. Squire was one of the most gifted and influential players of his time, the innovator who almost single-handedly introduced the idea of “lead bass,” conceiving and playing dynamic lines that complemented rather than doubled drums or guitar, both marking rhythm and carving out melody lines of his own. Take a song like the immortal Yes staple “Roundabout”; there are wonderful parts for all of the players and, like all of the best Yes music, it’s an ensemble piece with room for each to shine. But Squire’s perpetual-motion bass line is the linchpin of the entire concoction, a bounding beast that propels the band headlong through its memorable verses and choruses.

Many of Yes’ best pieces—“And You And I,” “Awaken,” and “Heart Of The Sunrise,” to name a few—are built around the musical tension between soft and loud, heavy and light, a tension that was physically personified in the small, airy Anderson and the Rickenbacker-wielding giant at his side. Squire seemed to instinctively grasp the energy and drama inherent in this musical tension, repeatedly finding the right moment in the band’s classic works to hold back, to create tension by not playing, before eventually releasing it with a volley of bottom-end thunderbolts.

Less often appreciated, but perhaps even more essential to the Yes sound were Squire’s harmony vocals. The secret sauce in the Yes recipe has always been their embrace of and facility with multi-part vocal harmonies, mostly arranged by former choirboy Squire. Listen to any of the classic tunes—“Close To The Edge,” “Yours Is No Disgrace,” even their one big radio hit “Owner Of A Lonely Heart”—and what’s striking is the way they arrange two and three voices into a series of melodic counterpoints that amplify dimension and impact.

Squire also had a fine voice on his own, as demonstrated on his one solo album. Still the best solo work any member of Yes has ever issued, 1975’s Fish Out Of Water places his keening lead vocals and inimitable bass work at the forefront of a trio that also featured founding Yes drummer Bill Bruford and then-current Yes keyboard player Patrick Moraz. Hearing him work an anthem like “Hold Out Your Hand” or the softer parts of songs like “Silently Falling,” you realize he could plausibly have taken on the lead vocal role on any of the occasions when Yes was without the services of Anderson, but he seemed to recognize that in the Yes context, his vocal talents were more valuable in a supporting role.

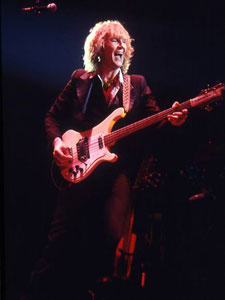

No appreciation of Chris Squire could be complete without a word about the man’s stage presence. From the winged bodysuits of the seventies to the silk pajamas of the oughts, Squire was always a magnet for the eyes on stage, easily the most flamboyant of his often stoic group, a natural showman who delivered every note with a fierce bravado.

The biggest hole Squire leaves for Yes, though, may be leadership. As every longtime fan knows, the internal politics of Yes—whose all-time roster now stands at 18 and counting—are complicated and fraught. Squire has always been the tentpole, the ringmaster-slash-personnel director who’s pushed the band forward again and again. In recent years I’ve questioned some of the decisions he’s made, but I’ve never questioned the man’s supreme musical gifts or commitment to and love of Yes music; that would be as inconceivable as his passing now feels. As fellow music writer Anil Prasad commented the other day, “I was occasionally one of the harsher critics of Yes’ latter day output. But you know why that was? Because I loved them that damn much.” Amen.

The biggest hole Squire leaves for Yes, though, may be leadership. As every longtime fan knows, the internal politics of Yes—whose all-time roster now stands at 18 and counting—are complicated and fraught. Squire has always been the tentpole, the ringmaster-slash-personnel director who’s pushed the band forward again and again. In recent years I’ve questioned some of the decisions he’s made, but I’ve never questioned the man’s supreme musical gifts or commitment to and love of Yes music; that would be as inconceivable as his passing now feels. As fellow music writer Anil Prasad commented the other day, “I was occasionally one of the harsher critics of Yes’ latter day output. But you know why that was? Because I loved them that damn much.” Amen.

Keeper of the flame though he has been all these years, I don’t think you can fairly say that Chris Squire was Yes; there have been too many other hands in that pot, stirring the waters and keeping them bubbling. It might be fairer to turn that around and say that Yes was Chris Squire—other than family and friends, it seems clear there was nothing of greater importance in his life than the band he co-founded and shepherded through 47 tumultuous years. Whatever aspirations those of us on this side of the equation might have had, it seems clear that the biggest fan Yes has ever had has always been Chris Squire himself.

Classic Yes keyboardist Rick Wakeman called Squire’s passing “the end of an era,” and it certainly is. I never imagined a Yes without Squire; I don’t think anyone can, at least not yet. But Wakeman also once said, somewhere in the depths of 1991’s YesYears documentary, that he could imagine a future Yes that would have no original members, and would exist simply to extend the band’s musical legacy to new generations of fans. This was all cheeky speculation at the time, of course; not so much now. We’ll see.

To Chris: thanks for your fire and energy, for your unique vision, and for a life well lived, in service of some of the most strikingly original and significant music of the rock era. Rest in peace, Fish. You’ve surely earned it.

It's the beginning of a new love inside

Could be an ever opening flower

No hesitation when we're all about

To build a shining tower

No explanations, need to work it out

You know we've got the power

- CS, “Parallels,” 1977.