Features

Colorful, Kinetic, Dangerous: Richard Fulco Explodes 1967

by Jason Warburg

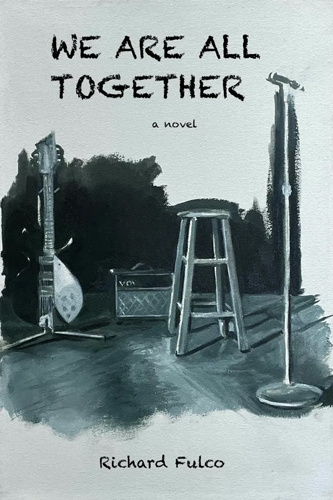

If the 1960s were a socio-cultural maelstrom, 1967 was the eye of that storm, the whirlwind inside of which a fertile popular music scene, the clash of generations, drugs, racism and political upheaval all collided hard with one another. If it feels like only one or two of those terms would need updating to capture the essence of the last few years in America, that might explain why Richard Fulco ’s new novel We Are All Together feels both very much of its time, and remarkably relevant.

If the 1960s were a socio-cultural maelstrom, 1967 was the eye of that storm, the whirlwind inside of which a fertile popular music scene, the clash of generations, drugs, racism and political upheaval all collided hard with one another. If it feels like only one or two of those terms would need updating to capture the essence of the last few years in America, that might explain why Richard Fulco ’s new novel We Are All Together feels both very much of its time, and remarkably relevant.

New Yorker Fulco’s previous novel There Is No End To This Slope followed the downward spiral of a thirty-something wannabe writer in present day; his new tale flips that arc to some extent by chronicling the Icarus-like trajectory of coming-of-age rock-and-roller Stephen Cane, who longs for “some kind of greatness,” only to encounter one potentially calamitous hurdle after another.

Through the bulk of the story—almost entirely set in the spring and summer of 1967—Cane is an eager 21-year-old full of late-adolescent ambitions that often blind him to the hazards of the company he’s keeping and the path he’s on. Having observed from afar his friend and former collaborator Arthur Devane’s rise to the verge of stardom as the psychedelic rock visionary Dylan John, Cane decides to split their hometown of Topeka, Kansas for New York City and the possibility of a reunion that could jump-start his own stalled career. “I know Dylan is great,” muses Cane, “and I want to be close to his greatness. Maybe some of it will rub off on me.”

Fulco’s portrayal of the wildly imaginative music-and-art subculture of 1967 New York is vivid and captivating, opening with an acid-tinged gig by Dylan John and his band Red Afternoon (a name lifted from Jack Kerouac’s On The Road) at the infamous Electric Circus. Fulco then mashes the accelerator through encounters with and/or references to Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Andy Warhol, the Velvet Underground, conscientious objector Muhammad Ali, and a prickly young music journalist by the name of Jann Wenner. Through it all the increasingly dazed-and-confused Cane plays the part of the small fish swept into deep water and swimming as fast as he can. Throughout his New York adventures Cane is surrounded by people who are seizing the cultural moment to try on new masks and personas; at times the more outlandish elements begin to feel like parody, but history tells us they aren’t.

At the same time, one of the book’s rare off notes is struck here, as Dylan John, who is as passionate about civil rights as he is disillusioned with the music industry grind, hooks up with and then abruptly marries Stephen’s mercurial ex, Emily, who is both a free-love hippie and an unrepentant racist. As much as the craziness of the times and the psychedelics coursing through everyone’s bloodstreams might explain that sort of opposites-attract match, as a reader I never could square that circle.

It's ultimately a minor point, though, in an unpredictable, entertaining fable about fame and ambition and jealousy and reconciliation. Upon landing his dream gig as the new guitarist for Red Afternoon, Cane responds in credible fashion for an in-over-his-head 21-year-old with a chip on his shoulder and serious daddy issues: he feels overwhelmed, acts out, sleeps around, and takes every drug that’s offered. From there we see Cane experience the highs of re-teaming with his musical brother-in-arms and playing a chaotic set at the iconic Monterey Pop Festival, in tandem with the lows of getting hooked on heroin and being kidnapped by a homicidal white supremacist cult led by a menacing Manson-like figure.

From there the tale only gets darker and stranger as Cane witnesses a horrific murder, escapes his captors, falls in with a pair of free-spirited travelers who he joins for a visit with Beat writer William S. Burroughs (Naked Lunch), and finally ends up in San Francisco’s infamous Haight-Ashbury district at the tail end of the Summer of Love. Fulco sketches the latter cultural moment in bold strokes, deftly capturing its beauty, flaws and contradictions.

As an experienced musician himself, Fulco has a good feel for the inside baseball of the music game as he portrays Cane playing a studio session and a live gig, navigating band politics, and dealing with professional jealousy, manipulative managers, and alternately fawning and spiteful fans. And he doesn’t shy away from the hard subjects so ever-present in 1967, particularly the endlessly charged topic of racism; there are tough moments and terminology used by characters that may feel like a slap in the face to the modern reader, but they are true to life and used in service of the larger point made in this story’s title, summed up late in Chapter 14: “We are all together in the struggle to survive in a mean, cruel and vicious world. Some of us got advantages. Some of us don’t.”

Through encounters with Janis Joplin, Sonny Rollins and George Harrison, scheming hangers-on and chanting Hare Krishnas, the initially brash and self-centered Cane comes to appreciate the need for a sense of purpose and set of core principles to guide the life he ultimately understands he is lucky to still have. Of all the elements of the Summer of Love that Fulco draws into his story, the one he captures the best is that sense of boundless ambition, the unconstrained and at times incomprehensible ways people acted out while searching for meaning and a way to center themselves. Some made it through to the other side, and some didn’t. Richard Fulco’s We Are All Together invites you to open your mind and take a trip through its kinetic, colorful, dangerous, and often strangely familiar world.