Features

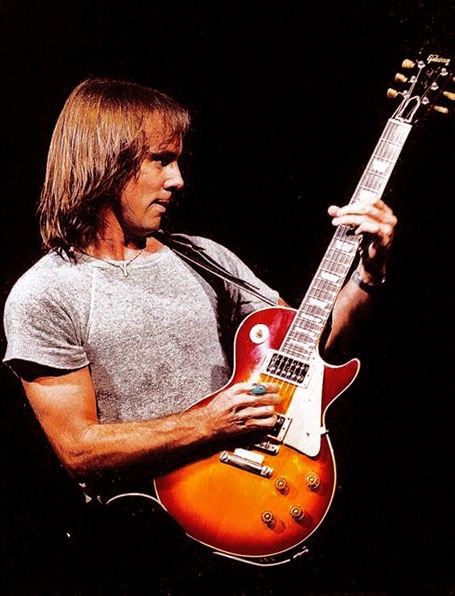

Ronnie Montrose's Uncompromising Vision: The 33-Year Odyssey of a Guitar Legend

by Jason Warburg

| One of the occupational hazards of being tagged as a guitar legend after your first album is that your reputation tends to precede you forever after. “Mercurial” is an adjective that’s been attached to guitarist Ronnie Montrose’s name so many times it’s almost a part of it. Add to that “innovative,” “enigmatic,” “technically brilliant” and most of all, “uncompromising,” and you’re closer to the complete picture. In a career spanning three decades, Montrose has confounded critics, managers, record companies and perhaps even, at times, his audience with albums that have over the years ranged far from the mainstream rock sound that marked the launch of his career. Montrose’s early session gigs with Herbie Hancock and Van Morrison paved the way for a stint in the Edgar Winter Band that saw him play on the monster instrumental hit “Frankenstein.” From there he went on at the age of 25 to found the seminal hard rock band bearing his name with Sammy Hagar, Bill Church and Denny Carmassi. Their first album, titled simply Montrose, remains a fresh and familiar air-guitar player’s icon 25 years after its release, which spawned such FM rock staples as “Rock Candy,” Bad Motor Scooter” and the blistering “Space Station #5.” |  |

From Montrose through the experimental guitar-and-synth band Gamma and a string of indie-label instrumental guitar albums, the one thing it’s become apparent Montrose has never been willing to do is compromise his musical vision. Right or wrong (to which a chorus of admiring fellow players would likely add, “Right!”), his relentless pursuit of new frontiers to travel with his instrument has never been less than interesting, however distant from the commercial mainstream it has taken him.

At least as intriguing as his stories about musical adventures with the likes of Hagar, Morrison and Winter, though, is the man’s keen sense of self. Back on the nightclub circuit, clearly in the second half of a career that once saw him fronting one of the biggest acts on the west coast, Montrose shows every evidence of having achieved a somewhat remarkable state of mind for a quote-unquote guitar hero. Call it self-awareness, or perspective, or simply maturity; Ronnie Montrose has no illusions whatsoever about what his dogged commitment to do it his way has cost him professionally and financially -- but neither does he have any regrets. He is at peace with the totality of his musical career to a degree that few artists who strain to grasp the brass ring ever achieve.

When did you first pick up a guitar? And when you did, did you know right away? Was it a “this is how I want to spend my life” kind of feeling?

It was. My friend had a guitar when I was 17. And the first time I held it, the first time my fingers touched the strings and I made a chord, I knew it was something that was resonant with me. I mean, I had friends who had saxophones and pianos, and while those were great, with the guitar there was something about the tactile connectedness, the left hand / right hand and wood and strings that just... worked. It was the pure joy of playing music with it and just strumming it that got me started. It certainly wasn’t “Wow, now I have something that I’m really going to be able to make a living with!” It had nothing to do with any idea like that. When I was 17 I just fell in love with it. And I’m 50 now, so it’s been 33 years. (Mel Brooks High Anxiety voice) “And they said it wouldn’t last...” (Laughter)

On the first few records you played on you played with Herbie Hancock, Van Morrison and Edgar Winter. What was it like starting out as the “new kid” and working side by side with big talents like that?

With Herbie Hancock I just went in and played sort of a wah-wah, Shaft rhythm guitar part. And as I recall, David Rubinson, the producer, even at a certain point worked the wah-wah pedal. I had the rhythmic right hand that I’ve been very fortunate to have. But I was completely out of my league and over my head and I was very aware of it, as was everyone else, though everyone else was cordial. And I had a great time. David Rubinson at that time was basically my mentor; he got me on some sessions and helped me a lot.

Van Morrison was the same kind of story. I had listened to Van, listened to “Gloria” and “Mystic Eyes” and all those songs I love. But I wasn’t aware of his absolute prowess over composition, how gifted he actually was as a songwriter. By no means was I on a level where I felt like I could interact with a talent like his.

It seemed like that same thing happened with Edgar Winter. For some reason -- and I’m sort of beginning to understand it as I grow and become somewhat “sage” myself -- you do seek out wise men. One of the reasons that Van and Edgar gravitated towards me was that I was fresh and talented and had lots of energy and a willingness to work within the parameters that were there and yet still add my own fire.

Let me ask about a song I heard on the radio the other day driving home: “Frankenstein.” How much fun was that to play on?

It was a lot of fun, because it was a thing that wasn’t supposed to be a single, it was just Edgar messing around on an ARP synthesizer. The reason we called it “Frankenstein” was that it was an assemblage of parts of different songs Edgar had been working on. There were a couple of parts that were actually from Edgar’s Entrance album. The whole thing was just a gothic rock showcase for Edgar’s newfound fascination with the synthesizer. It was amazing to hear that thing on the radio in its day. Of course, in hindsight everyone knows exactly why that was a smash single, because sounds like those synths and effects were just unheard of in a power rock format.

Did you have any inkling at all when you wrote and recorded that first Montrose album what a lasting impact and long shelf life it would have?

Absolutely none. We had a couple of managers come up and listen to me, Sam, Denny and Bill play “Rock Candy,” “Rock the Nation,” “Space Station #5” and “Bad Motor Scooter” at rip-roaring levels. And one management agency went out and had a meeting and then came back in and said, “Guys, if this were 1968, we probably could do something here, but this isn’t going to work. You might want to think about changing your music and getting up with the times.” At which point we just kind of closed ranks and adopted the attitude that was that band, which is, “If you like it, fine. If you don’t, take a hike. We’re playing this music, and we love this music.” Oh, the folly of youth and testosterone. (Laughter)

What would you consider the highlights of the whole Montrose experience -- both incarnations, with Sammy Hagar and with Bob James --

(Laughter) Sammy is funny -- he calls the first two Montrose albums THE Montrose albums, and the third Montrose album the FIRST Bob James album. And in a way, bless his heart, he’s right, because there is no “Montrose” without me and Sam and Denny and Bill, in my mind. And only later have I come to realize that. Everyone knows that. It’s like any seminal band -- without the original members, it just isn’t the same. I don’t care what incarnation it is -- and this is just me editorializing here -- but there is no Deep Purple without Ritchie Blackmore and Ian Gillian. Original members make up a band, and when bands have that big of an impact on the general consciousness, any other incarnation is pale and historically irrelevant.

You guys did a little mini-reunion for one song on Sammy’s last album. Would you ever consider trying it again, for an album or a tour?

There’s been talk about it. We’re not quite sure if it could work or not for all of us. If it happens, it seems like this year may be better suited for everyone than anytime. Getting together with all four of us in the studio was like a high school reunion. It was great because we had a chance to catch up and talk about everything, not just the record business or even music. We talked about our families and the other things going on in our lives. Ten years ago I would have told you (a reunion) would not be a possibility. Now I can’t say that. Now I would say that it could be a possibility.

After four albums of fairly heavy rock and roll with Montrose, you first solo instrumental album Open Fire caught a lot of people by surprise with its string section and mandolins and Edgar Winter’s jazzy keyboard textures. Was that your intent? Were you consciously trying to go a different direction and challenge your audience with the music on that record?

Most assuredly not. I was consciously trying to make the music that I felt like making at that time. That particular musical foray was completely comfortable and natural to me, much to the dismay of those in the music “business.” Open Fire did, however, afford me wonderful recognition from [highly respected jazz drummer/bandleader] the one and only Tony Williams, who recently passed away. So while many of my rock fans were not too pleased with that record, I was pleased and honored to be invited to travel to Japan with Tony Williams, who wanted me to play on his The Joy of Flying album. That’s the thing -- any situation is potentially double-edged, where music is concerned.

In 1979, when the Open Fire phase was done and Gamma was coming together, were you still thinking maybe you’d get back to instrumental music down the road?

Yeah, never a doubt, because playing melody and chord structure sans lyrics has always been so deeply a part of me.

Gamma put out three albums of amazing music in a pretty short period. What were the highlights for you of that band and that experience?

The first Gamma record was great for me because I was writing and playing at a very fast pace. Working with Ken Scott [producer of Gamma 1] was great because we were experimenting, and I was afforded the chance to go off on all kinds of little sonic forays. Like, for example, the intro to “I’m Alive” was a microphone tapped against my knee and processed through a vocoder. Also a lot of different guitar tones and chord changes and fun sonic experiments. And it was great, the energy of that lineup. It was the original Gamma lineup, and once again, I guess there was an essential quality to it.

There were good and bad parts working on all three Gamma albums, but another highlight was doing the third Gamma album [Gamma 3], because I was working with Mitchell Froom and we were experimenting quite a bit. And also, we were bucking the system -- management and the record company were trying to get us to play the “Let’s make a single” game, and it was fun engaging in combat with that mindset and saying instead “Let’s make interesting music, and hope it comes out well.”

At a certain point after Gamma ended, you went in the direction of all-instrumental albums. You had to know that was not the recommended career path if your only priority was to have a big commercial success.

I can’t state it any clearer than to say that I was following my muse. Everyone tried to steer me into making popular music, from any manager I was with to any record company I was with, and in fairness, understandably so. Because without an artist who makes popular music, management and record companies and booking agents don’t survive. So as a result, you’re faced with the dilemma of saying, “I know I should be doing this kind of music, but I don’t feel like it.”

So in the end, I just followed the music, for better or for worse. I’m not saying I’ve made brilliant instrumental solo albums, but I certainly have taken the path that seemed appropriate to me at the time. In hindsight, are there things I would change on my records? Sure. Are there approaches I would take differently? Yes. But that’s what any artist would do.

One of the rewards for making instrumental music has been that, at one point, I was in a period of making records where I reached a serious existential moment of self-doubt. I was making records that I knew were not going to get played on the air a lot, just working off the knowledge that there were enough people that enjoyed this music that I could survive. But it almost got to the point that I’d make records and I’d get them out and get no response.

And you need some kind of response. If you write a review, you like to have somebody go, “Hey, nice review.” If you repair a car, you like to have somebody go, “You know, you did a damn fine job on that car.” Or you paint a house -- you know what I’m saying? When you do something, it’s important to get feedback. And I reached a point where I specifically remember sending out Mutatis Mutandis, or maybe The Diva Station to magazines and newspapers and industry people, and signing a little note saying, “Call me back and let me know what you think,” just to get their feedback. And, as God is my witness, I got not one single response to my mailings. Not even to say “I don’t like it.” Zero response. And that was a pretty low point for me.

But now, the reason I’m so up and so joyful in spirit is that, because of this wonderful world of e-mail, I’ve gotten e-mails from across the country and around the world from people who specifically write to tell me about The Speed of Sound or Mutatis Mutandis or The Diva Station or other records that I’ve done, and say, “You know, that record really touched me. That got me through some tough times.” And that, right there, period, end of story, is all I need; I am a happy man because of that. Because I know somewhere, the music that I’ve made has touched and reached -- I don’t care how many people -- as long as I’ve gotten through to someone. That’s all we all hope for, really, is that sort of validation.

The Mr. Bones album is really unique and fun in that it works as a video game soundtrack -- I can almost see what’s going on on the screen in my head -- and it also works as an instrumental guitar album. Tell me how you got involved in that project and what it was like working on it.

It was a long project. The producer of the [video game] project told me that it would take six months, and it literally took two years. I never thought I’d work on a project for two years.

Going into it, they wanted this game to be guitar-based. It was different from other games because of that, because Mr. Bones is a guitar player, and the whole thing is based around guitar playing. [Video game producer] Ed Annunziata’s original concept for the game was nothing but guitar and a lot more of the sort of Southern old blues guitar, but that’s not my nature. We sort of found our levels after he invited me into the project. He never imagined the music could go that far out in different areas, and different forms, but it all made sense. And I guess that’s sort of what I do with instrumental music and synthesizers and the things I’d done with Gamma, is take the music to those different levels.

Mr. Bones was also great for me to flex my underscoring ability, which I’ve always known I had. I just sort of dove into it. All the music on the segue parts between the game levels, those were me, and I knew that I could do them. Ultimately, I’m sure I will end up composing music for films.

The making of the Mr. Bones CD was one of the most fun times I’ve had in the studio for a while, because it came at a point where I’d worked long and hard though an arduous journey from beginning to end of the video game project. And after all that work was done, the fun was getting to put great musicians together and not specifically play music for the game, but rather to take these sketches of music from the video game and make a bona fide full-length CD. It was fast, it was loose, and it was a lot of fun.

Tell me about the concept and process behind your new live album. What made you decide it was time for a live album?

We actually recorded it right before I did Mr. Bones. I was playing live with my then-studio band, Michele [then Graybeal, now Montrose, on drums] and Craig [MacFarland, on bass]. We were just sort of having fun playing live trio music, and a really long-time old friend of mine named Jim Mathews suggested, because he had some recording equipment, that we go out and record a few gigs. And we tried it, just for the fun of it, and one night just happened to be spectacular. It was totally loose, raw. It was a packed house -- a small crowd, but it was packed -- and it was a magical night.

And the reason I haven’t finished it before now is, of course, that I was working so hard on Mr. Bones that I didn’t have time. The [live] tape’s been around for a couple of years, but we just got to the point now where we could go back and finish it.

At first, because of the temptation of multi-track, I was going to say, like a lot of guitar players do, “Well, a live album is a live album, but I’ll just go back and fix this little guitar note.” It dawned on me later that that was the absolute wrong thing to do. Now it’s against my philosophy, which is, let the mistakes stay where they are. That way the listener will get the same exact experience as the people who were there having a great time at the concert got, as opposed to the listener getting sort of an “edited for TV” experience. And it’s called Roll Over and Play Live.

What tracks are on the album?

Different pieces of music from my instrumental albums. A lot from Music From Here, which was my current album at the time, plus a couple of older songs and about a half dozen new songs we wrote in rehearsal specifically for the shows.

You’ve explored a lot of territory as an instrumental artist; do you think you’ll ever try the rock-band-with-vocals setting again?

I may not do the rock band with vocals, but I will absolutely do the vocal thing again. I’ve been working with a great artist recently, a singer-songwriter named C.J. Hutchins. I’m producing his record for him out at my home studio, and we’re basically finishing the mixes right now. His project is called Out of These Hands, which is the name of a song that he and I co-wrote. He brought me 40 songs and let me pick the cream of the crop, and I gave him song chorus ideas, and he was absolutely brilliant at coming up with the appropriate verse and the right feel and nuance.

It made me realize that I really do love working with lyrics and working with singers. My problem is -- one of these stigmas for me is -- when a singer who’s looking for a guitar player hears the name Ronnie Montrose, they immediately think, “Well, I better start screamin’.” You know? “I better start to cinch it up, and try to scream and I better cop a pose.” But that’s not where I’m at at all right now with lyrics and vocals and songs in general. So I’m very much looking forward to doing a vocal album, but it won’t be a vocal album that is a rehash of Montrose, it’ll be a vocal album that is where I’m at now, currently. It’ll be a collaboration with someone who’s at the same place I am right now, which is hopefully at a deeper lyrical level and less rock-oriented.

What’s the difference for you between playing electric and acoustic? What do you usually use to compose on?

Basically, composing, there’s hardly any difference between electric and acoustic when I compose a melody or a chord structure. But there is an attitude that seeps in when I compose at 100 decibels. There’s a certain thing that comes out, maybe a powerful passage of chords that you wouldn’t find at home with an acoustic guitar. But really, for me they’re pretty interchangeable.

Tell me about your plans for your website, and what kinds of things people are going to be able to find on it when it’s up.

Wow! I can’t even believe it! I’m so stoked! The website is going to be www.ronnieland.com. It’s going to have an editorial page, obviously, because I’m a long-winded kind of fellow. (Laughter) And lots of great photos, and some features about things that have happened in my life. I’m also really enjoying exploring the possibility of getting my music out to people on the website. One of the great things about the website and Internet is that I’m able to network with people who are looking for my music or for other music and sort of be the catalyst that connects people to find my music or any other music. There’ll be a bunch of my CDs, and some downloadable audio... and that’s about as specific as I can get right now. We’re just now roughing out all the features.

Do you have any sort of target date yet?

How about yesterday? (Laughter) My son Jesse, who is a programmer, is helping me set it up, as is my wife Michele, who is not only a talented drummer, but a gifted illustrator and artist and is creating a real look and feel on the site. One of the prerequisites for site was we all agreed we did not want it to look like it came from a “Website Building 101 kit.” Instead of using standard graphics, we’re using a lot of hand-rendered art.

I’m also looking forward on the site to connecting people and getting feedback from people about both specific and not-specific things. It might be “What chords did you play on this song?” but it also might just be being a catalyst for dialogue.

Another interesting thing that has happened to me with this world of e-mail and the Internet is that I’m finding it very easy to discern who has legitimate questions about things. The way I figure it, if you’re backstage at a concert, you sometimes meet people where you can carry on a wonderful conversation and dialogue with them... and then sometimes you’re meeting a person who’s had quite a bit too much to drink, and who’s shaking his fist and going “You rock, dude!” I just figure that, when I get a letter from someone who is pretty proficient on a keyboard and can articulate themselves, I’m probably going to be able to communicate with them. So e-mail has been a wonderful filter. Not there’s anything wrong, mind you, with “You rock, dude!” (Laughter) I don’t mind that. It’s just that, that’s the level that conversation is going to stay at.

What other guitar players do you admire the most? And what do you think of instrumental guitar artists like Joe Satriani and Eric Johnson?

It’s an interesting thing that happens with guitar music; it sort of waxes and wanes. I’m at the point now where, anytime anyone succeeds in any way playing any type of instrumental guitar music, I’m gonna stand up and cheer. I’m long past that point -- I think it’s kind of a youthful thing -- looking at guitar music as a competition, or guitar playing as calisthenics or gymnastics. I’ve sort of left that mentality and mindset by the wayside. It’s not that I’m being diplomatic, it’s just that I think that mindset is sort of horrid.

That having been said, I do, like anyone else, have certain tastes. So I can tell you that the players that I listen to and enjoy are players like Adrian Legg, Chris Rea and Billy Gibbons. My complete hero is Daniel Lanois. My dream come true would be for Daniel to be able to produce a record for me, because he takes an approach that I really, really enjoy, which is just such a non-slick approach.

There’s an album he produced for Emmylou Harris that had a completely different sound that I thought was wonderful for her.

Uh-huh. Absolutely. And his album For the Beauty of Wynona is just a devastating record. Some of the finest guitar tones I’ve heard. If you don’t have it, you should get it, as well as the Sling Blade soundtrack.

Sounds like I’ve got some shopping to do. Okay, last question. You’ve put some really interesting, thought-provoking little quotes and phrases on most of your albums since Gamma 2 in 1979. The last one, on Music From Here, says: “The only path to the here and now is the one that we have traveled.” Are you where you want to be? Is there anything you’d change if you could?

That’s really the point of the quote. Once you realize you can’t change things, that you’re going to be here and you’re going to be now, it’s pretty difficult to stray off that path into worrying about what might have been.

How that quote came about is that I was sitting there at one point thinking “You know, there are a lot of things I would change.” But pretty soon I realized, had I gone to an “investor” a few years ago, or done the “economically sound thing,” buy a house and build up equity and do all of those things, I wouldn’t be talking to you right now. I wouldn’t be married to the woman of my dreams right now. I would have never met people and friends that I have now. And I wouldn’t be playing the music that I’m playing right now.

All of us can look back and say, “I should have done this...” and -- and this is what irritated me at the time -- it’s all based on this idea of success. People say, “Well, if only Ronnie would have done this...” -- and it’s not just me they’re saying that about, it’s any artist who hasn’t succeeded to that level of making a string of gold or platinum records. The music business is based on that, and of course everyone wants to rationalize their value system and say “Well, at least it’s a quality record.” But to that mindset, a quality record means nothing in and of itself.

So when people were saying “Where did Ronnie go wrong? Why didn’t he go the gold and platinum record route?” I started thinking about it, and I looked around at all the wonderful things in my life right now. And I thought, had I gone down that road, I never would have met the people that I know now, and have the family and friends around that I have now. The other side is that, if you’re not now where you want to be, then the awareness that you’re the one who’s taken the path to where you are can remind you that you have the ability to go where you want to be.

The bottom line is this: I am very -- no, extremely -- happy. I’m healthy, I have a wonderful wife, my children are doing great, I have wonderful friends, and I’m playing music. Everything is good in my life. The only thing I could use... is a little more money! Like everybody else! (Laughter) And since that’s my only problem, I don’t really have any problems right now.

#