Features

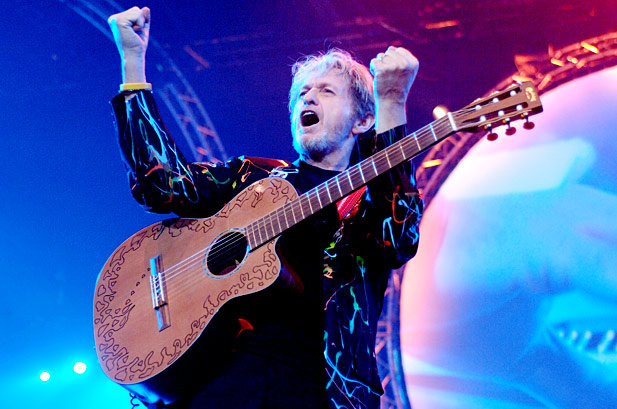

Jon Anderson of Yes: The Daily Vault Interview

by Jason Warburg

Jon Anderson will always and inevitably be best known as the co-founder, lead voice and lyricist for iconic progressive rock band Yes. The group’s flights of musical fancy, tenacity, and rough-and-tumble internal politics have all become legend over the past very eventful 45 years. Those at-time bruising politics resulted in Anderson’s replacement in 2008 by a tribute band singer, since replaced himself by current Yes vocalist and Anderson soundalike Jon Davison. Anderson himself seems to have taken this tumult in stride; there were a few understandably bitter words in the immediate aftermath of his ouster, which took place while he was too ill to perform, but since then he has expressed nothing but openness to whatever the future may hold, while pursuing a terrifically productive solo career. First came Survival and Other Stories, a solo album cataloguing his recovery to good health and musical rebirth, then the 2010 duo album The Living Tree with fellow Yes expatriate Rick Wakeman, extensive touring both with Wakeman and on his own, and more recently the release of “Open,” an Internet-only 20-minute single carrying echoes of the classic Yes long-form symphonic prog approach.

One thing it’s apparent the 68-year-old Anderson will never do is stop creating new music; it’s simply in the man’s blood. Taking a break from crafting the follow-up to “Open,” Anderson describes by phone the sunny patio overlooking the ocean he is occupying not far from his San Luis Obispo home, announcing that “I’ve been in the studio for the last six hours, but I had to get out of there!” Much like his free-form lyrics, his sentences don’t always flow in predictable ways. What shines through is that his intention, his spirit, is as strong as ever, his vivid imagination rich with ideas and insights and visions that emerge in one intense burst after another. A half hour spent on the line with Jon Anderson is a travelogue of musical adventures led by a man who was born to create, and has had a hand in producing some of the most memorable musical moments of the rock and roll era. From watching the Beatles play in Liverpool, to conceptualizing an app containing his entire musical catalog, in his lifetime, Jon Anderson has truly seen—or imagined—it all.

The Daily Vault: Looking back on your career, you’ve been making music for 50 years now. How does that feel?

Jon Anderson: It’s amazing! You know, I was talking to a young friend today called Alvin, who comes up every month to work on his guitar playing—he plays and writes some beautiful guitar concertos. He’s only 18, and I reminded him that I started when I was 18 years old with my brother’s band The Warriors. It was like, the beginning of the beginning of opening the doors of modern times. After the Beatles came out with a single called “Love Me Do,” my brother and I went to see them play up near Liverpool, and there they were, four guys on stage playing amazingly well. I think they’d only got two microphones and that was the sound system, but it was amazing. And everybody sang, and everybody screamed, and everybody enjoyed the show, and from that moment, I just wanted to be a Beatle, I think. Like a million other people! [Laughter]

A member of our writing staff suggested a question that I’d like to ask about your lyrics. He said that your lyrics tend to suggest rather than describe scenes, and emotions, and drama, and create moods and textures with sound, rather than using more standard narrative approaches. And he was wondering, what were the seeds of somewhat abstract but very emotional songs like "Yours Is No Disgrace" or "Awaken"?

I think that, more than anything, I realized when I started writing songs that I would write lyrics that were sort of free-form. I knew what I was trying to say, but I didn’t really want to say it, I wanted to free-form it. I’d sing a song the first time around and then listen to the cassette and try to figure out what I was trying to say. I’d write things down and look at them later and say, “Well, these are metaphors for something”—how I was feeling about Vietnam, or how I was feeling about music and peace and love, feeling still like a hippie from the ’60s. “Yours Is No Disgrace” [from 1971's The Yes Album] really had a lot to do with Vietnam, and the world changing, and how things like wars are really out of our control. A lot of the time people feel incredibly guilty for the things they’ve gone through and really, we should not feel disgraced, because it’s part of the life experience. “On a sailing ship to nowhere, leaving any place” is the earth—we’re on a sailing ship that flies around the sun, and it’s not going anywhere, it’s going round and round.

“Awaken” [from 1977's Going For The One] is from another important time. By the end of the ’70s I’d come to terms with feeling that I was learning about spirituality more and more, and I felt that I had to wake up, and that I wanted to sing about waking up. So I wanted to call a song “Awaken,” because I was going through an awakening feeling, that feeling of connection, which wasn’t really anything I could put my finger on. It wasn’t really anything to do with any one religion; it seemed to have a lot to do with all religions, sort of all interconnected somehow.

I was reading some of your recent interviews this week, and one quote in particular jumped out at me [from an interview by Vintage Rock]. You told a wonderful story about the School of Rock kids who wanted to play “Awaken” with you, and the story finished with this comment: And someone said to me: “Why did you do Tales From Topographic Oceans?” I said, “Well, if we hadn’t done that, we wouldn’t have done ‘Awaken’.” And I have to confess that personally, I’ve never been a huge fan of Topographic Oceans, but if that’s what it took to produce “Awaken,” it was worth every minute.

It’s interesting, because people ask me why we did Topographic, period. And it’s because we were left to our own devices, and music was a very open book to the band, and I was wanting to experience an adventure in music rather than writing music for the radio. We’d had some experience writing songs and hoping they would get played on the radio, but radio was—“Oh, we’re not going to play that, it’s eight minutes long, we don’t play ‘And You And I,’ and ‘Close to the Edge,’ we’re not going to play that.”

And it was like, “Well, screw you, then.” Because music is not just making money, music is all about the experience and the adventure. And when we did Topographic, I really jumped into that incredibly big well of the musical experience, and I can only say that 25 years later, we performed the first movement [“The Revealing Science Of God: Dance Of The Dawn”] and the last movement [“Ritual: Nous Sommes Du Soleil”] of Topographic with a full orchestra, and it went down incredibly well, audiences around the world loved it. This was about 2001 or 2002 and it just reinforced that music is really a lot more about creation rather than how much money you make out of it. It’s funny you mention you weren’t particularly keen on it, but I understand. But if you listen to “Revealing,” it’s 20 minutes long and it’s my wife’s favorite piece of music—and she wasn’t a Yes fan!

It was painful to admit that to you, because I love so much of the work that you and the band have done. Topographic was tougher for some of us, more of a challenge for the audience.

Oh, yeah! Sure. And it was a challenge for us to create, and I would say in interviews that, whatever we learned, the audience will learn along with us, and it might be good, it might not be great, but at least it’s ours.

I’d like to ask a little about “Open.” Over the course of your career you’ve seen the music industry go through wave after wave of change. And here you are presenting this big, 20-minute suite of music as an Internet-only release, and I’m wondering how you see the future of the music industry unfolding, both in terms of your own career, and in terms of all the artists who are just starting out today who are trying to figure out how to break through and have an impact.

Well, like everything, I think necessity is the mother of invention. When I came to realize that record companies were not interested in my work anymore, I tried to use the Internet as a vehicle, and then I realized there are thousands of people doing it, it’s not just me. My website doesn’t have that much music on it, just about 12 tracks, but then I started thinking about creating an app that I could use to put all this music up I’ve been creating in the last ten years. And then I want to evolve that app, and create a situation where people can get new music every month, and then every six months they’ll get albums that they’ve never heard from me before, with Vangelis or by myself. The idea is that within the next five years, the app itself will have probably all the work I’ve ever done, and be up to 12 or 14 hours long.

That’s an amazing concept.

And the idea would be to “visualize” everything, so that not only are you listening to music, you’re actually seeing a visualization of it at the same time. In the ’60s you had those lights at gigs in San Francisco with bands like The Doors, they were just projections at first and then it evolved over the years from projection to these large scale giant TV monitors you have all over the stage now, and you’re getting incredible visuals using computer animation. I think that’s part of the experience of the 21st century, music as a visual experience as well.

“Open” seems to echo the scope and structure of some of the longer Yes works that we were just talking about. Could you talk about how it came together, and what the process of creating it was like? I know you worked with other musicians over the Internet.

Right. I’d recorded an album called Survival and I had about 30 or 40 songs that I’d written with different people around the world. So I picked out a dozen for an album, and then realized that one album really wasn’t enough to express how I felt. I released it and it did pretty well, and a lot of people liked it.

And then I thought, “I think I should try a long-form piece,” because it’s part of my DNA to do long-form pieces. I was the one who pushed the band into doing long-form pieces. It’s an interesting story, because when Close To The Edge was released in ’72, there was a lot of FM radio in America, and they would play the whole album. Within six months of it being released, FM radio was no more, because it wasn’t making much money, it was really a lot of collegiate radio. It wasn’t good business for regular stations, so they stopped playing long-form music.

And in a way, that made me want to do even more long-form pieces, I just wanted to rebel against the idea, that they wanted to restrict us, just because our music isn’t making them enough money, because they wanted to sell advertising space. During the period it was a really difficult experience. But over the years I’ve contended that music can be a journey, and that’s why I decided to do “Open,” because I really wanted to say to myself, “I can create another journey.” And that’s what I did.

“Open” is essentially an orchestral piece. I was curious what led you in that direction, rather than using more traditional rock instruments as you did in the long-form pieces with Yes. Was that in any way a carryover from the experience of making Magnification [the 2002 album featuring Yes with an orchestra]?

Probably. Magnification was a good experience, I enjoyed it, and I enjoyed touring that music. I just knew that I had a friend who lived 20 minutes away named Stefan Podell, who’s a beautiful orchestrator, and we’d been talking about doing some work together for about three years. I just did a sketch of the whole piece on guitar, and then gave it to him, and he came back about two weeks later with a beautiful sketch of the orchestration. And the more he did, the more I wanted, so it became more about the orchestra, and I just loved the idea. I’m actually working on a second one now. This next one is called “Ever” and I might have said there would be no orchestra this time, but I just put an orchestra on it this morning! It’s kind of betwixt one and the other right now.

Do you think you’ll eventually release these two long pieces on a CD, or do you see yourself moving more in the direction of Internet-only releases?

I think I’m just going to work toward Internet releases and using the app right now. But there’s a record company that’s releasing all the classic Yes stuff, Audio Fidelity, and they’re a very, very nice company and if they wanted to release some of my work I’d be very happy to work with them. I’ve even thought about vinyl as well, for fun.

On a different subject, we lost [founding Yes guitarist] Peter Banks recently. I read somewhere that you had been in touch with him not too long ago. And I just wondered if there were any particular memories of Peter that you’d like to share.

Peter was a really nice guy, and he was in the band with Chris when I first joined that band, called Mabel Greer’s Toy Shop. And Peter came up with the name Yes. I kept saying “We’ve got to have a short name, Mabel Greer’s Toy Shop is so long.” And so one day I said “Why don’t we call ourselves Life?” And Chris said, “Well, let’s call ourselves World.” And Peter said “Why don’t we call ourselves Yes?” And we looked at him and said “The Yes?” And he said, “No, just Yes.” And so that was it, and it was like, “cool.”

And for a couple of years Peter was with the band, and everything was going really well, and then we got to a time when I wanted to rehearse 24 hours a day and not everybody was into that. I felt, we’re lucky to do what we do, and we should rehearse every hour, minute, second God has given us. And that didn’t go over too well with Peter, and it came to a point after that where we had to start thinking about bringing someone in, and we found Steve Howe. It was hard to let go of Peter. He didn’t really like working out the structures much, while I was more into structure every day, though I don’t really know why.

Over the years I kept bumping into Peter and we’d always say “Hi, how’re you doing,” and then a couple of years ago we got in touch because a friend of mine got in touch with him and he wasn’t very well. So I sent him an e-mail and we talked two or three times last year, and talked about doing some songwriting, and he said “When I get better, I will.” His health wasn’t good. And then I spoke to him early this year, I think it was in February. And things happen, you know, life moves along and people go off to the next world. I’m sure he’s happy.

When you did The Living Tree album with Rick Wakeman a couple of years ago, the setlist on your tours included a number of Yes songs. Was it a special challenge to take those songs out of the band context and reinterpret them in a duo setting? Did that freshen up the songs for you as a performer?

I think it made it an interesting way of presenting a song, just with a piano and guitar. It was great with Rick, because he’s such a talented piano player, and the songs always seemed to sound great, and the audience loved hearing them. Of course, when you’re not in the band, you have to decide, do I perform songs I wrote for the group, or not? But I love singing them, and I wrote them for the group, and the audiences want to hear them, so there’s no harm in doing that.

On the subject of Rick, there’s a question I’ve wanted to ask for years: is Rick Wakeman in fact the funniest man ever to be in Yes?

He’s funny, he’s crazy, he’s really off the wall! He’s Monty Python and Benny Hill put together. He’s a really good guy.

There have been rumors for a couple of years now about a joint project that you and Rick and Trevor Rabin were working on. Can you give us an update on that?

Well, I made the mistake of mentioning it once, and obviously a lot of people want to know what’s happening, and it was just one period of time about a year and half ago or so when I was seeing Trevor quite a lot and we’d been writing a couple of songs and we talked about maybe working with Rick. It’s funny because you spend time talking ideas and then six months later you’ve stopped talking about them, and then Rick’s busy and Trevor’s doing another movie and I’m on tour. It was very hard to bring it together, and at the moment we’re sort of in limbo.

Shifting gears again, I’m curious what your thoughts are about the relationship between a popular artist like yourself and the fans. People like Neil Peart of Rush have written songs about the strangeness of that relationship; his line [in “Limelight”] was that he couldn’t “pretend a stranger is a long-lost friend.” Have you had any particularly interesting experiences in bridging that gap between performer and fan?

The thing about fans is, we’re all the same people, we’re all connected on so many different levels. We’re all connected through music, and when I meet somebody in the street, or in a store, I’m always very happy to meet them and always happy to make them feel good and relaxed, because I know what it’s like.

I was over in Australia just now and there was Paul Simon, and it was very hard to even say hello. It’s Paul Simon, you know? And I said hello, and he shook my hand, and I said how are you doing, and he said fine. It was lovely, but it was very brief. I’ve been in that situation where I’ve met somebody that I really admire and it’s daunting! So, whenever I meet any fan, whatever age they are, I’m always happy to make them feel at ease and I say to them, “I’m a fan too.” I love what we’ve done in Yes, I’m so proud of what we’ve done, and why not?

That’s a wonderful story about Paul Simon, knowing that you guys covered “America,” and what that must have meant to you to meet him.

Yeah, it was a trip! If he’d stopped and we’d started talking, I wouldn’t have been able to say very much, because, you know, it’s PAUL SIMON!

To work with Rick and the band—well, I said to Chris the other month, if Geoff [Downes] and Jon [Davison] are in the band too, I don’t mind, you know, we can all work together. I’m very open. I think the music is more important, and the fans are more important than all that “I want the band to be my way” business. I was never into that. And I’m always very open for things to work out okay.

Rick is a very important part of the group. He was part of the special development musically of the band and I think that it’s important that he should be involved as well.

And I spoke to Alan a couple of weeks ago. So we’re in touch, and when the time comes, when the stars align, we’ll probably be able to get together and perform together. I don’t see myself going on crazy tours for months on end, I don’t see the point in that—we’re all a lot older, and I hope a lot wiser. We should do shows here and there and we should make sure the shows are very important and very, very well produced, something we can look back on and say, well, we really did it.

There was one other statement I wanted to try out on you and maybe you could just react to this. With all due respect to every one of the musicians who has been a part of Yes over the years, my personal feeling is that the band has almost always felt like it’s greater than the sum of its parts, and that whoever has been in the band at any given point has done some of the best work of their career as part of Yes. I’m wondering if it feels to you like there’s something about being in Yes that challenges people to raise their game to the highest level.

My whole feeling about the band is that we are very talented people, we are very lucky to do what we do, and we should work really hard to put on a great show, because the audiences deserve it. And the music should never be restricted to trying to have a hit record, because that’s for other people to do. Yes music has its own energy, its own style, it’s a unique, one-off thing. There’s not many bands that can do Yes’ kind of music; I don’t actually know anybody that does the kind of music that Yes has done over the years. It’s been very adventurous and very progressive music, and I think that’s fun to look back on, especially now, and say that we did certain things that were really daring, that we took the road less traveled.

#

Many thanks to Billy James of Glass Onyon PR for his assistance in arranging this interview.