Features

Andy Summers: A Life In Music

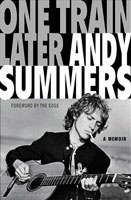

Police guitarist delivers One Train Later

by Jason Warburg

| There’s a familiar feeling I get when reaching the end of a book I’ve really enjoyed. It’s a bittersweet, slightly disorienting sensation of departing -- against your will -- a world that’s thoroughly captivated you, even if some part of you knew all along that your time there was destined to be limited. In this insightful musical autobiography, guitarist Andy Summers shares in intimate detail how he came to experience that same sensation, arriving -- after great tribulation -- at the peak of a legend-making career with the Police, only to face the inevitable yet all-too-soon breakup of the band that transformed him from a rock and roll footnote into a global superstar. One Train Later -- so named out of karmic respect for the chance meeting on a train with Police drummer Stewart Copeland that would change the course of Summers’ life forever -- is hardly an “insider's expose,” though. Rather, it’s a knowing rumination on the joys and trials of a life devoted to making music, told with self-effacing and thoroughly endearing wit. Every person who picks up this book knows where it is headed -- to the collision of Summers, Copeland and bassist/vocalist Sting and their 1979-1983 ascendance into the ranks of rock demigods -- but the journey turns out to be at least as interesting as that glittering destination. |  |

Summers speaks frankly but unsentimentally of a difficult family life as a child, dwelling only long enough to establish the roots of a passion for making music that blossomed from the first time he held a battered old Spanish guitar: “It is an immediate bond and possibly at that moment there is a shift in the universe because this is the moment, the point from which my life unfolds. I strike the remaining strings, which make a sound like slack elastic. It’s horribly out of tune and I don’t know even the simplest chord, but to me it is the sound of love.”

From that pivotal moment, Summers tracks forward into his adolescent initiation into the secret brotherhood of chord-sharing among poor teenaged Brits who learn by ear off the radio and a handful of LPs; no lessons, no music books. His adventures as a young adult, after moving to

Through this period Summers relays anecdote upon wonderful anecdote -- told with a rich mixture of classically British deadpan humor and entirely appropriate amazement – of life in the mid-60s

The path to the top is hardly a straight one, though. The vicissitudes of the rock life eventually land Summers in

From there, things take off like a rocket. The acceleration of the narrative parallels the acceleration of the life being lived within it. Things spin faster and faster and faster until it becomes dizzying. Gigs, tours, recordings, singles, more gigs, press, fans, more recording, and the rocket leaves the launch pad and heads off into its well-chronicled orbit. It feels like a matter of weeks -- though in fact it was three years – before Summers the struggling, near has-been guitarist with wife and child finds himself a single, rootless millionaire rock star, drowning his celebrity sorrows on a shroomed-out madman’s safari across the

The beauty of this book is that Summers, having been to the mountaintop and returned to tell the tale, appreciates in equal measures the glorious affirmation and the absolute insanity of life in the rock and roll circus. He renders in vivid detail the rapid disconnect from the everyday, the protective bubble in which one must exist or be rent limb from limb by one’s ravenous, hysterical “fans,” and the seductive, destructive nature of the machine which works 24/7 to feed both itself and the egos of the trio at the top. Managers are carted off to jail, marriages disintegrate, and wild times and assorted odd injuries ensue (note: it’s always handy to have an ENT on your small

For all that, Summers the author never loses sight of what propelled him -- his passion for the guitar and for the power of music as tool of self-expression, spiritual exploration and connection with an audience. Fittingly, the book proper -- embellished with a brief afterword -- ends not with the band’s breakup but with the band launching itself onstage at Shea Stadium in August 1983 to play the first concert there since the Beatles. “We walk into the center, the luminescence, the incandescent blaze of electric power, and there is a deep roar like the end of the world. Eighty thousand lighters go on in the stadium, an incendiary salutation. Like a prayer, it is now, it is forever. I strike the first chord.”

For the curious, Summers is frank but generally kind when speaking of his former bandmates, and contrite about his failings as a husband and father. Sting does come off as aloof, controlling, and taken with his own celebrity, but that hardly qualifies as news. Summers still speaks of him (and Copeland, for that matter) with the affection of a long-time mate who stood shoulder to shoulder with him more times than toe to toe.

Writing entirely in the present tense -- a device which lends immediacy to every moment -- Summers renders one scene after another with a rich mixture of clarity and bemusement, conveying both the intimate details and, with the benefit of twenty years’ perspective, the greater significance and/or absurdity of any given situation along his twisting path. One Train Later is a captivating ride through both a musical era and a life made in music, narrated by a gifted storyteller -- a treat for any music lover, and essential for any Police fan.